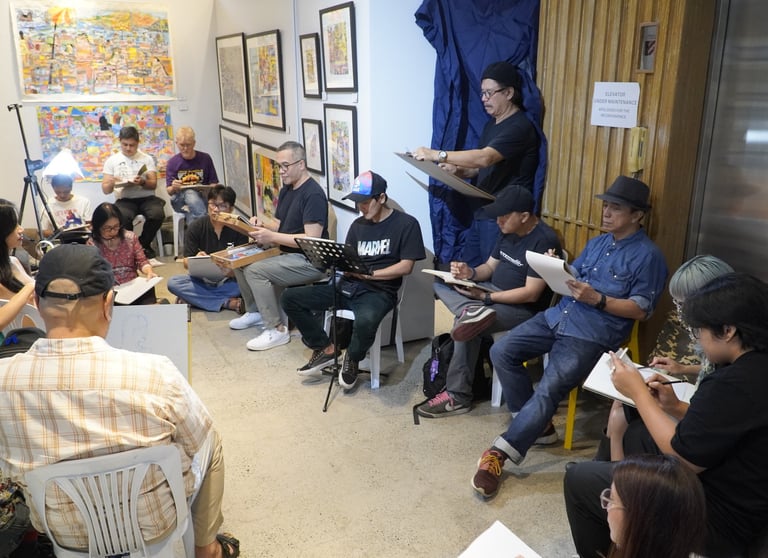

Nude Sketching: Building Representational Skill and Individual Style

An overview of the importance of regular life drawing session for a visual artist.

10/9/20256 min read

1. What is nude (or life) sketching

Life drawing or nude sketching refers to drawing (or painting) from a live model who is unclothed. It has been a foundational training practice in Western and many other art traditions for centuries. The aim is not only to replicate human anatomy and form, but to observe gesture, light and shadow, texture, proportion, and the subtleties of the human figure in space.

2. How nude sketching hones an artist’s representational skills

There are several interlocking ways life drawing strengthens representational ability:

Anatomical and structural knowledge – Regular practice forces the artist to understand bones, muscles, how limbs connect, how bodies bear weight, etc. This understanding gives a foundation so that if parts are stylized or abstracted later, they still “work” visually. For example, Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo used dissection and sketching of cadavers to understand the internal structure of the body.

Proportion, gesture, and balance – Observing the whole figure in dynamic or restful pose helps the artist internalize ratios (torso:limbs, head:body, etc.), rhythm of line, weight shifts, and how gestures convey movement or rest. The quick-gesture sketches (short timed poses) train perception of the essential line or curve of a pose, before getting lost in detail. Various art instruction texts (such as The Natural Way to Draw) emphasize this.

Light, shadow, surface and three-dimensional form – Nude forms reveal surface undulations, how light plays across curves, planes, skin folds; how shadows wrap around volumes. Unlike clothed models, nude figures make the transitions of form more visible. This helps with modeling, shading, understanding of value, and visualizing form in space. Life drawing forces the artist to look in 3D, not flatten.

Observation, seeing and perceptual accuracy – Drawing from life sharpens the eye: noticing subtleties in contour, edge, negative space, foreshortening, perspective. Photographs tend to flatten or distort; life drawing trains sensitivity to spatial depth and visual relationships. Many artists and instructors insist that nothing replaces observing a live model.

Speed and economy – Because life drawing often has timed poses (e.g. quick gestures of 1-5 minutes, then longer poses), the artist learns to make fast decisions: what to omit, how to mark form with minimal lines, how to suggest shape without detailing everything. Over time an artist becomes more fluent and economical in mark-making.

All of these feed into stronger representational art—where the goal is to depict forms, light, atmosphere, texture etc. in a convincing way.

3. How nude sketching leads to re-interpretation and personal visual style

While nude sketching starts with observation and realism, it often becomes a fertile ground for personal reinterpretation and style formation. Here’s how and with examples:

Experimentation with form, gesture, and distortion

Once an artist has internalized anatomy and proportion, they can begin to bend, exaggerate or abstract them for expressive effect. Egon Schiele, for example, produced nude drawings that are distorted, elongated, contorted; the gestures are intense, almost tortured, yet they maintain a kind of anatomical logic. His style is recognizable in the sinuous outlines and expressive distortions.Focus on texture, line quality, and surface

Artists like Gustav Klimt created thousands of graphite and ink nude sketches; in these, contour, the sensuousness of line, and the way bodies occupy space, become aesthetic ends. These studies fed into his more decorative works as well.Visible process and composed structure

Euan Uglow is a good example: he painted from life, used careful measurement, often left in the evidence of his construction (grid marks, measurement indicators), creating a tension between the living flesh and the constructed space. Over time that method becomes part of his style—how he balances geometry, proportion, and painterly surface.From representational to expressive: psychological content

Lucian Freud is often cited: his nude figure paintings are deeply realistic, but also full of psychological density. His long sittings, the modelling of flesh, the slowness of surface rendering—all come from strong representational practice, but are used to convey presence, intimacy, sometimes discomfort. The realism is not neutral—it is reinterpreted.Rejection, or transformation, of idealisation

Classical tradition often idealized the nude (perfect proportions, ideal beauty). Many modern and contemporary artists transform that ideal: they retain structure but include blemish, weight, asymmetry, aging. Nude sketching gives them a basis to observe the real, before choosing what aspects to idealize / stylize. Jenny Saville is one modern example: she uses life drawing, but her nudes are massive, visceral, sometimes raw. Her lines, textures, flesh tones are part of her personal aesthetic.Accumulation of visual vocabulary

Frequent sketching builds up an internal catalogue of poses, forms, light-values, textures. Over time an artist draws less from direct observation and more from memory, recombination, imagination—but still rooted in what’s been observed. Style becomes a filtering of what the artist notices and prefers. Also choices about line weight, how to render shadow, whether to smooth or leave visible the brush or pencil, all become part of one’s style.

Their sketches, studies of anatomy, dissections etc. built unsurpassed understanding of form, light, proportion.

4. Examples in history

Here are specific artists and specific works or practices that illustrate both representational sharpening and style development:

Michaelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci - Their sketches, studies of anatomy, dissections etc. built unsurpassed understanding of form, light, proportion. In their finished works one sees both ideal and expressive qualities: e.g. Michelangelo’s sculpture and figures in the Sistine Ceiling combine ideal proportions with dynamic gesture; Leonardo’s sketches of anatomy feed into sfumato and soft modelling.

Egon Schiele - Life drawing are majority of his drawings; constant practice of nude sketches from models/self. His style is highly recognizable—ebb and flow of line, contorted bodies, expressive distortion; raw emotion.

Euan Uglow - Painted from life models, made measuring part of his method; visible structure in his nudes. His style emerges through precision, but tempered with painterly subtlety; a tension between measurement and flesh, geometry and organic form.

Philip Pearlstein - Known for realist nudes, returning repeatedly to drawing and painting nude figures, often in quiet, non-romantic settings. His style is very much about seeing: bodies as forms in space, anatomy, light; he often avoids symbolic or allegorical overlay—so the style emerges in the way he sees and composes rather than as dramatic alteration.

Klimt - Thousands of nude model drawings; much of early work around line, contour, erotic pose. His decorative style, use of ornamental pattern, the way he frames the figure, etc. grows out of line and gesture, but becomes transformed.

5. Research / Studies

A study by Rostan (2010) looked at children aged 9-15 in an art program, comparing observational life drawing tasks with imaginative drawing; it found that more exposure to observational drawing is strongly correlated with greater artistic ability and motivation. In other words, the discipline of looking, measuring, representing a real figure helps build both skill and confidence.

“Six ways that life drawing improves you” (Melbourne Art Class) lists improving fundamental drawing skills; visual proportions; rhythm and harmony; fluency in drawing; speed; seeing light and shadow—practical benefits of consistent life drawing.

Survey of figure drawing books (e.g. Figures From Life: Drawing With Style) show that many instructors emphasise combining representational accuracy with individual expression: gesture, line quality, choice of pose, lighting, etc.

6. Key tensions and how they help style

Accuracy vs interpretation: The more you know the form, the more you can choose which parts to simplify, distort, omit, exaggerate. This tension often produces original style.

Speed vs detail: Quick sketches encourage loose, expressive marks; longer work allows refinement. Balancing both gives variety in style.

External observation vs internal memory/imagination: Over time artists move from drawing purely what is in front of them toward internalizing form, memory, and imagination. The combination allows style to emerge uniquely.

Ideal vs real: Traditions of ideal beauty (e.g. Classical, Renaissance) vs realism that includes imperfections. Many artists move from training in ideal forms to representing what they actually see in flesh—wrinkles, blemishes, weight, asymmetry—and that becomes hallmark of their style.

Conclusion

Nude sketching (or life drawing) remains one of the most potent ways for an artist to develop representational skills: in anatomy, proportion, light/shadow, perspective, gesture. But importantly, it is not a static path toward perfect realism. Once the groundwork is strong, life drawing also becomes the laboratory in which an artist reinterprets, distorts, experiments—and so discovers or refines their own style. The combination of disciplined observation + individual choice, accumulated over time, is what turns technical skill into expressive, recognizable artistry.